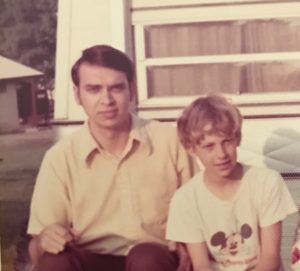

Parents do the best they can with what they are given. At least that’s what I’ve been told, and I believe it’s true for most parents (not all). Given this benchmark, my dad has done remarkably well. It doesn’t seem to me that he had any sort of role model for what it means to be a dad.

My grandfather was an abusive alcoholic. Dad once pulled me aside and confided to me about his dad. He said, “Do you see that quiet old drunk sitting in his chair all day? I just want you to know that person is not the person I grew up with.”

As a child, Dad’s older brother would tease him about his stutter. According to Dad, this is why he retained his stutter throughout his life. He blames his stutter for never getting promoted to plant manager at his job.

I don’t mean to give the impression that my dad blames others for his problems. He doesn’t. I merely want to give a few examples of how my dad had a tough life.

He doesn’t talk about it much, because talking about it opens up emotions that he would rather not re-experience. My own experiences as a child taught me that I could shield myself from negative emotions too. Like father, like son. Dad recently had two strokes, and I notice that he seems to express more emotion these days.

In my family, positive emotions were OK, and negative emotions were not OK. The main negative emotions I was aware of growing up were shame and anger. Mom would stand me in a corner; Dad would spank me. Before you judge my dad, remember that times were different back then. For instance, my junior high school gym teacher would paddle students. Could you imagine that happening today? Dad always made sure he calmed down before administering a spanking. I believe he didn’t want to be like his dad, who I’m sure would act out of his anger.

I always wondered why I was so angry as a teen. After all, I had a good family who provided for me. There was no addiction, abuse, or any other reason to believe that my family was anything but normal. Yet my anger bubbled up and I lost control on more than one occasion. I kicked a hole in my bedroom wall. I put the heel of my hand through a window. I acted out and got arrested.

My dad would scold me repeatedly for leaving toys out and otherwise not keeping the house neat and clean. I would feel ashamed, but it wouldn’t affect my behavior. My dad couldn’t understand why I left a mess all the time and neither could I. Today I think it was my way of rebelling. If this was my motivation, then I was completely unaware of it as a child.

When I was a pre-teen, my parents took me to see a psychologist. It may have been because I wasn’t socializing at school, but that’s just a guess. They stopped taking me after that first appointment. I found out years later that my parents couldn’t afford to have me continue counseling. I don’t blame them. Best I could tell we were lower-middle class, and they were doing the best they could.

Our house was too small for a family of five, so he tore he off a portion of the roof and created a large dormer upstairs. That gave us an extra bedroom and bathroom. He got help from family for the main structural stuff, but he finished all the interior himself. It took him years.

Dad tried to teach me what he knew. He would make me watch as he designed a new sunroom or worked on the car. I would get bored, and eventually he gave up. He had better success with my brother, and Dad continued to help him with home remodel projects until his recent strokes.

Dad worked his way up the ladder. His first job was packing light bulbs at the nearby General Electric plant. He worked his way up to draftsman, and finally was recognized for his skill diagnosing and fixing problems with machinery. He was made a Quality Control Engineer despite the fact that he didn’t have a college degree.

Years later when he left GE, he applied at a local plant for an opening for Quality Control Engineer. They were barred by policy from considering his resume because he didn’t have a degree. He found a job at a local truck radiator manufacturer. They were having terrible problems with quality control, and he was able to get a handle on it. After he retired, the company retained him for a time as a consultant for much higher pay.

I only found out much later some of the other things Dad sacrificed for me and my family. I remember him taking night classes toward a college degree. Recently Mom told me he gave that up because it took away too much family time.

My parents moved us from Ohio to Mississippi just before my senior year. Part of the reason is because our schools were tough and I would get bullied. My lack of socialization meant that there was nobody to say “good-bye” when I left the only home I had ever known. As desolate as it felt, things did get better during my time in Mississippi.

Dad was always a family man, and he loved to take us traveling on vacation. Even as small infants he took us all on vacation. At first we tent camped and later Dad purchased a travel trailer. He was a purist—no TV in the camper. It was a treat when we camped at a KOA because they had a pool and utility hookups. I would look longingly at places Dad called “tourist traps.” (I never did get to “See Rock City.”) We traveled across the U.S. and back. By the time I was a young adult I had been to 46 states.

Dad became assistant scoutmaster at my boy scout troop. Every summer we spent a week at Beaumont scout camp. We also took week-long trips to high adventure camps, such as Tinnerman canoe base in Canada and Philmont backpacking camp in New Mexico.

Dad recently told me, “There’s nothing more important than family.” It’s one of the very few times I’ve ever seen him tear up.

After I graduated college, this frugal man suddenly became generous, simply giving me money when he got the opportunity. He’s still giving away his retirement savings. I wondered, what happened to the man I grew up with? I concluded that he wanted to be generous all along, but waited until I was responsible.

Responsibility was a major value to him, something that he passed along to all his children.

So it’s like I said at the beginning: Dad, you have done remarkably well with what you were given. You may not have known everything I needed as a child, but what you did know you gave. For my part, I was pretty ungrateful. From the age of 16 I couldn’t wait to get out of the house. Yet I chose a local college and was home almost every weekend.

You’ve told me repeatedly that you’re proud of me. It’s taken me a long time to say this, but know that I’m proud of you too.

To be completely honest, if my dad wasn’t my dad, I don’t think I’d take the time to really get to know him. We’re so different. If that sounds harsh, I’m don’t mean to be. If anything, it simply means that Dad knew that his children didn’t have to be his best friends, and that made him a better parent.

I think my parents still wonder if I still hold a grudge against them for my childhood. I don’t. Because I have my own issues opening up and expressing my emotions, I don’t think they can read me very well. I hope this letter is a start to me doing things differently.

I was given a gift after Dad had his strokes. For months it appeared his mind would never come back. He doesn’t remember almost a year of his life. But his mind did come back. What he lost was mostly physical: the ability to see and walk well. He retains his sense of humor. He tells me every time I see him that he really enjoys my company and wants to see more of me. If he hadn’t come back, I wouldn’t be able to read this letter to him. How many people get a second chance?

Leave a Reply